Saturday, February 2, 2013

Scandals: The Emma , the Panamint and More

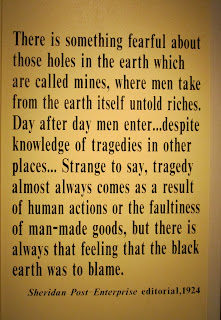

Plaque on display at the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne, Wyoming

Scandals threatened Stewart’s career in both his legal and political lives. He

made and lost fortunes along the way. Stewart had little to his name when he died. The

money came and the money went. He never had enough to keep up with his millionaire

cronies like Leland Stanford and William Ralston. Stewart invested often in mines, but it

was a risky business. The first mining disaster came in December 1861 when his

Virginia City mine flooded. Stewart took a secretive trip to San Francisco in terrible

weather to secure a loan from an old friend named Chris Reis. Census figures show

Reis in San Francisco, but not with an extensive fortune. It is conjecture, but perhaps

William Ralston might have been involved with the loan. The two could have met when

Stewart passed through Panama since Ralston worked there five years. At any rate,

Stewart headed back to Virginia City with borrowed money to settle his debts. He

eventually sold the mine and recouped most of his original investment.

The Emma Mine, located in Utah, sullied Stewart’s reputation although he avoided

legal penalties. The damage to his reputation outweighed the money he made. Ralston

had an early interest in the Emma. Neither Stewart nor Ralston could stay away from

mining ventures. Ralston could have bought the mine with his friend Asbury Harpending

for a mere three hundred and fifty thousand dollars. They decided the mine was “nothing

more than a large kidney and of little value.” Unfortunately, Stewart did not come to this

conclusion. James Lyon, two other prospectors, and Stewart worked to develop the Emma.

The others soon forgot Lyon and sought wealthy foreign investors in England. Since the

speculators spread rumors of the mine's value, many clamored to buy the stock. Lyon

hired Stewart to represent his interest in the mine. Stewart told Lyon he would get him

five hundred thousand dollars as his share. Stewart traveled to England with a speculator,

Trenor Park. In a few months Stewart appeared to be on the other side ending up as a

board member of the Emma with Park and several other well-known British

politicians. Stewart made a fortune on the deal with Lyon coming out as the big loser with

but two hundred thousand dollars as his share. Eventually news came out that the Emma

was a sham with hardly any silver. The experience spoiled English investments in North

American mines for years to come. Lyon never forgave Stewart; for years he wrote nasty

letters and filed lawsuits that never came to fruition. He claimed Stewart built the Dupont

Circle mansion with money that should have been his.

Stewart and his partner Senator John P. Jones believed the Panamint Lode located in Death

would be the new Comstock Lode. Investors from Los Angeles rather than San Francisco

financed these mines. Stewart and Jones let Trenor Park join them, despite his reputation

from the Emma Scandal.

A big problem was transportation to and from the Panamint area. Stewart and Jones

made an agreement with bank robbers. Desperadoes who discovered the silver in the first

place agreed to pay back twelve thousand dollars taken from the Wells Fargo Company.

However, the Wells Fargo Company refused to transport bullion from the two

Panamint Mines – the Wyoming and the Hemlock. Always one to think outside of the

box, Stewart had the silver bullion formed into seven hundred and fifty pound balls. The

thieves could not steal them when Stewart had large wagons move the treasure. The

rutted roads through the Sunrise Canyon out of the Panamint area caused travel to be a

challenge. Panamint investors made some money, but not enough. Production began

during August 1875. The Panamint boom lasted a mere three years and did not live up to

the lofty expectations of Stewart and Jones.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment