William Morris Stewart lived from 1825 to 1909. I am proud to say he was my great-

grandfather's brother, and a dynamic individual who made many significant contributions

to the history of the United States as a United State Senator.

As a young child Stewart lived near the newly built Erie Canal in New York. The

family moved to Mesopotamia, Ohio in 1831. His precocious mind inspired him to seek

adventure from an early age. Stewart’s life included many successes as well as defeats.

He made and lost fortunes during his lifetime because of his addiction to investing in

mining schemes.

Historians credit Stewart with being the Father of Mining Legislation and

the person who worded the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution. He faced

challenges in mining, law and politics with intelligent ferocity.

The title Angles, Dips and Spurs refers to the single ledge theory of location of silver

that Stewart advocated in the mountainous Comstock area of Nevada. formerly Utah

territory. Stewart proved the theory in court and earned thousands of dollars in

litigation fees. Stewart played the angles of every situation in his life. Mining scandals

were the dips in his experiences. Financial backers who gave up on Stewart tended to

spur him on with even riskier plans. Stewart was purportedly the model for the figure at

the top of the mountain in the painting Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way by

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze; the picture hangs in the United States Capitol Building.

Stewart served as a United States Senator from Nevada for twenty-eight years.

The following stories about William Morris Stewart illustrate the scope of his life in both

positive and negative ways. He interacted with many fascinating historical figures

such as Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, Ulysses S. Grant, William Ralston and William

Sharon.

Angles, Dips and Spurs

Saturday, February 2, 2013

The Journey Begins

William Morris Stewart requested permission from his father to work at a neighboring

Ohio farm until haying time. “Why certainly, you can go and stay as long as you have a

mind, and you need not come back any more unless you wish to."

come back any more unless you wish to.” His mother Miranda overheard the conversation

and begged her husband to take it back. William, barely a teenager, packed his meager

belongings and left his family in 1839. He journeyed many places during his lifetime

supporting himself by sweat, determination and genius. Father and son battled because

William desired more schooling than the school year of three months offered in

Mesopotamia, Ohio. William saved the money from his farm work and moved to nearby

Farmington to attend an academy. The schoolwork did not challenge him as much as his

lack of social skills. The hulk of a boy did not fit the furniture. His popularity exploded

when other students discovered his math ability. Before long he taught the younger

children and tutored his peers. A year later William paid for his sister Mary to

attend the academy, too. He supported both of them by working for a local farmer.

In four years William left Ohio permanently to attend a large high school in Lyons,

New York that prepared students for university education. Stewart’s name appears with

over five hundred other students on the 1845 student roster. Stewart was the only scholar

from Ohio. Stewart studied hard and continued his education at Yale, where his

preparatory education at the Farmington Academy and the Lyons Union School served

him well. Once again he excelled in mathematics; he even proved a Yale textbook

had a mathematical error in it. He attended Yale for a a year and a half.

The California Gold Rush was more compelling to him than his schoolwork. Judge

Sherwood, a supporter from Lyons, offered him transportation money to make the trip.

Stewart sailed on the steamer Philadelphia from New York City in January 1850.

Turbulent storms raged on the trip, causing most passengers to turn green and take to their

bunks. Stewart helped the crew after huge waves damaged the ship. By the time the

Philadelphia reached Panama, the sun came out and the waters calmed. The next leg of

the trip meant crossing the Isthmus of Panama on a small boat with three others plus four

indigenous Panamanians maneuvering the craft. Stewart managed to get one of the few

tickets left on the ship Carolina for the journey from Panama to California. The ship

was overcrowded and they suffered because of a lack of enough food and water. Stewart

had a quarter in his pocket when he landed in San Francisco five months later. San

Francisco teemed with the possibility of untold riches. Stewart tried to make money by

gambling, but preferred working on the wharf. He earned enough to take a steam boat

ride to Sacramento. Shortly after arriving a fever attacked Stewart; he refused a trip to the

unsanitary hospital, instead using all his strength to ride another boat to Marysville.

Some kind Samaritans put him on a bed of straw near the Deer Creek Stream. He lay

there for eight days looking more dead than alive to passers-by. He drank gallons of water

from the icy stream. When the fever broke, Stewart got up and started his new life near

Nevada City, California.

Stewart amassed his first fortune not just from mining, but aiding other miners with his

Grizzly Ditch business, a forty-mile canal apparatus that provided water needed for placer

mining. He also spent many hours reading law with John McConnell, a California lawyer

with expertise in mining law. The combination of experiencing the life of a miner and

learning the ins and outs of mining law gave Stewart the ticket to making lots of money.

Ohio farm until haying time. “Why certainly, you can go and stay as long as you have a

mind, and you need not come back any more unless you wish to."

come back any more unless you wish to.” His mother Miranda overheard the conversation

and begged her husband to take it back. William, barely a teenager, packed his meager

belongings and left his family in 1839. He journeyed many places during his lifetime

supporting himself by sweat, determination and genius. Father and son battled because

William desired more schooling than the school year of three months offered in

Mesopotamia, Ohio. William saved the money from his farm work and moved to nearby

Farmington to attend an academy. The schoolwork did not challenge him as much as his

lack of social skills. The hulk of a boy did not fit the furniture. His popularity exploded

when other students discovered his math ability. Before long he taught the younger

children and tutored his peers. A year later William paid for his sister Mary to

attend the academy, too. He supported both of them by working for a local farmer.

In four years William left Ohio permanently to attend a large high school in Lyons,

New York that prepared students for university education. Stewart’s name appears with

over five hundred other students on the 1845 student roster. Stewart was the only scholar

from Ohio. Stewart studied hard and continued his education at Yale, where his

preparatory education at the Farmington Academy and the Lyons Union School served

him well. Once again he excelled in mathematics; he even proved a Yale textbook

had a mathematical error in it. He attended Yale for a a year and a half.

The California Gold Rush was more compelling to him than his schoolwork. Judge

Sherwood, a supporter from Lyons, offered him transportation money to make the trip.

Stewart sailed on the steamer Philadelphia from New York City in January 1850.

Turbulent storms raged on the trip, causing most passengers to turn green and take to their

bunks. Stewart helped the crew after huge waves damaged the ship. By the time the

Philadelphia reached Panama, the sun came out and the waters calmed. The next leg of

the trip meant crossing the Isthmus of Panama on a small boat with three others plus four

indigenous Panamanians maneuvering the craft. Stewart managed to get one of the few

tickets left on the ship Carolina for the journey from Panama to California. The ship

was overcrowded and they suffered because of a lack of enough food and water. Stewart

had a quarter in his pocket when he landed in San Francisco five months later. San

Francisco teemed with the possibility of untold riches. Stewart tried to make money by

gambling, but preferred working on the wharf. He earned enough to take a steam boat

ride to Sacramento. Shortly after arriving a fever attacked Stewart; he refused a trip to the

unsanitary hospital, instead using all his strength to ride another boat to Marysville.

Some kind Samaritans put him on a bed of straw near the Deer Creek Stream. He lay

there for eight days looking more dead than alive to passers-by. He drank gallons of water

from the icy stream. When the fever broke, Stewart got up and started his new life near

Nevada City, California.

Stewart amassed his first fortune not just from mining, but aiding other miners with his

Grizzly Ditch business, a forty-mile canal apparatus that provided water needed for placer

mining. He also spent many hours reading law with John McConnell, a California lawyer

with expertise in mining law. The combination of experiencing the life of a miner and

learning the ins and outs of mining law gave Stewart the ticket to making lots of money.

Mark and William

Samuel Clemens, AKA Mark Twain, and William Morris Stewart Stewart crossed

paths several times during their lives. Eerily similar in personality traits, they could not

stand each other. Both Stewart and Twain wanted to make fortunes and control situations.

They did not always tell the truth in their autobiographies. Clemens showed up in

Carson City in 1861 along with his brother Orion. President Abraham Lincoln appointed

Orion to be the territorial secretary. Sam came along for the ride and the possible

opportunity to make a few dollars. With his talent for writing he soon became employed

at the Territorial Enterprise, one of Nevada’s many newspapers. The witty Clemens

expanded and exaggerated the political news. The politicians who generated his stories

frequently suffered abuse in his columns. Readers loved the humorous adaptations of

Clemens, which only served to egg him on to become even more outlandish. Clemens

soon picked up the name Mark Twain. During this Comstock period Twain invented a

Third House of Representatives. He set himself up as the governor. When he reported

about the Third House, he skewered William Morris Stewart, a politician given to lofty

rhetoric. Stewart kept making the same speech over and over when he campaigned

against taxing the mines during the first constitutional convention. One time Twain

thundered, “Take your seat, Bill Stewart,” because he had heard the same speech so many

times he could recite it himself. This did not go over well with Stewart. Neither he nor

Twain cared to be the victim of a joke.

It was generally accepted practice to bribe journalists to write about new silver

mines in order to get more investors. Miners promised a few shares or certificates in

exchange for good press. Stewart and Twain had an agreement regarding a new mine.

Supposedly Stewart never gave Twain the money he owed him. Twain claimed fraud.

He finally paid Stewart back in Roughing It by portraying Stewart with an eye patch,

making Stewart appear to be a pirate.

Twain did not leave Annie Foote Stewart alone either. She loved giving spectacular

parties. He delighted in describing her numerous social events in great ridiculous detail.

Twain made fun of her clothes, her friends and the food she served. Stewart got even for

this by arranging for Twain’s stagecoach to be attacked on a trip between Carson City and

Virginia City. The desperadoes roughed up Twain and stole his money and his

pocket watch. When Mark Twain returned to Virginia City, he went to a bar to tell his

story. His so-called friends bought drinks for everyone using Twain’s money. He figured

it out when he got his watch back. Twain left the Comstock shortly after he explained to

readers he had been involved in one of the greatest robberies ever carried out in the west.

It is hard to believe Stewart would associate himself with Mark Twain more

than once, but they could not stay away from each other. Senator Stewart hired Twain as

his secretary in Washington D.C. Some thought Stewart liked the prestige of having a

world traveler work for him since Twain had recently returned from Europe. At this time

Annie was on a world tour so Stewart rented rooms at 224 “F” Street at the corner of

14th. The landlady, Miss Virginia Wells, was a prim and proper spinster. Stewart

told Twain he could write his current novel on the premises as well as serve as his

secretary at a salary of one hundred eighty dollars a month. He even offered his cigars

and whiskey to Twain, which turned out to be a bad move. It was not long before Twain

played tricks on poor Miss Virginia – or perhaps he was just being himself. Twain drank

heavily, wandered through the house at nighttime and even smoked in bed. Miss Wells

threatened evictions for both of them. Following a tongue-lashing, Twain vowed to

behave. That was a promise he could not keep. Aside from the bad behavior with the

landlady, Twain began answering the letters of constituents in very creative ways. One

town wrote to request a post office. Twain questioned why in his response - no one

knew there anyway; what they needed was a jail! The backlash from

constituents infuriated Stewart. Twain and Stewart parted company soon after.

Stewart mentioned Twain in his autobiography. “I was confident that he would

come to no good end, but I have heard of him from time to time since then, and I

understand he has settled down and become respectable.” Twain and Stewart had more in

common than they cared to admit. Both had an indomitable spirit and had no problems

taking off for extensive journeys. Twain traveled to the west, farther west to Hawaii and

also to the Holy Lands. Stewart left home at an early age with his travels taking him back

east from Ohio to New York, Panama, the west and to Europe several times. They both

became national figures, and were both sometimes successful and sometimes to the point

of financial insolvency. They both spent lavishly, especially on houses.

E Clampus Vitus was an odd organization similar to the Masons but with fewer rules

and regulations. The group began in California in 1851. The members, known as

“Clampers”, tended to be the crowd that favored drinking, carousing and high living in

general. It suited the newly developed west. Twain and Stewart joined the group. In fact,

Stewart started the branch in Virginia City. The group had power in numbers. Some say E

Clampus Vitus helped Stewart get elected as the first Senator from Nevada.

The biggest difference between the two giants came toward the end of their

lives. Twain turned bitter and his writings reflected this. Stewart never gave up on the

dream of finding just one more big silver mine. He traipsed around Nevada on a mule

looking for silver his eighties. Stewart remained the eternal optimist.

paths several times during their lives. Eerily similar in personality traits, they could not

stand each other. Both Stewart and Twain wanted to make fortunes and control situations.

They did not always tell the truth in their autobiographies. Clemens showed up in

Carson City in 1861 along with his brother Orion. President Abraham Lincoln appointed

Orion to be the territorial secretary. Sam came along for the ride and the possible

opportunity to make a few dollars. With his talent for writing he soon became employed

at the Territorial Enterprise, one of Nevada’s many newspapers. The witty Clemens

expanded and exaggerated the political news. The politicians who generated his stories

frequently suffered abuse in his columns. Readers loved the humorous adaptations of

Clemens, which only served to egg him on to become even more outlandish. Clemens

soon picked up the name Mark Twain. During this Comstock period Twain invented a

Third House of Representatives. He set himself up as the governor. When he reported

about the Third House, he skewered William Morris Stewart, a politician given to lofty

rhetoric. Stewart kept making the same speech over and over when he campaigned

against taxing the mines during the first constitutional convention. One time Twain

thundered, “Take your seat, Bill Stewart,” because he had heard the same speech so many

times he could recite it himself. This did not go over well with Stewart. Neither he nor

Twain cared to be the victim of a joke.

It was generally accepted practice to bribe journalists to write about new silver

mines in order to get more investors. Miners promised a few shares or certificates in

exchange for good press. Stewart and Twain had an agreement regarding a new mine.

Supposedly Stewart never gave Twain the money he owed him. Twain claimed fraud.

He finally paid Stewart back in Roughing It by portraying Stewart with an eye patch,

making Stewart appear to be a pirate.

Twain did not leave Annie Foote Stewart alone either. She loved giving spectacular

parties. He delighted in describing her numerous social events in great ridiculous detail.

Twain made fun of her clothes, her friends and the food she served. Stewart got even for

this by arranging for Twain’s stagecoach to be attacked on a trip between Carson City and

Virginia City. The desperadoes roughed up Twain and stole his money and his

pocket watch. When Mark Twain returned to Virginia City, he went to a bar to tell his

story. His so-called friends bought drinks for everyone using Twain’s money. He figured

it out when he got his watch back. Twain left the Comstock shortly after he explained to

readers he had been involved in one of the greatest robberies ever carried out in the west.

It is hard to believe Stewart would associate himself with Mark Twain more

than once, but they could not stay away from each other. Senator Stewart hired Twain as

his secretary in Washington D.C. Some thought Stewart liked the prestige of having a

world traveler work for him since Twain had recently returned from Europe. At this time

Annie was on a world tour so Stewart rented rooms at 224 “F” Street at the corner of

14th. The landlady, Miss Virginia Wells, was a prim and proper spinster. Stewart

told Twain he could write his current novel on the premises as well as serve as his

secretary at a salary of one hundred eighty dollars a month. He even offered his cigars

and whiskey to Twain, which turned out to be a bad move. It was not long before Twain

played tricks on poor Miss Virginia – or perhaps he was just being himself. Twain drank

heavily, wandered through the house at nighttime and even smoked in bed. Miss Wells

threatened evictions for both of them. Following a tongue-lashing, Twain vowed to

behave. That was a promise he could not keep. Aside from the bad behavior with the

landlady, Twain began answering the letters of constituents in very creative ways. One

town wrote to request a post office. Twain questioned why in his response - no one

knew there anyway; what they needed was a jail! The backlash from

constituents infuriated Stewart. Twain and Stewart parted company soon after.

Stewart mentioned Twain in his autobiography. “I was confident that he would

come to no good end, but I have heard of him from time to time since then, and I

understand he has settled down and become respectable.” Twain and Stewart had more in

common than they cared to admit. Both had an indomitable spirit and had no problems

taking off for extensive journeys. Twain traveled to the west, farther west to Hawaii and

also to the Holy Lands. Stewart left home at an early age with his travels taking him back

east from Ohio to New York, Panama, the west and to Europe several times. They both

became national figures, and were both sometimes successful and sometimes to the point

of financial insolvency. They both spent lavishly, especially on houses.

E Clampus Vitus was an odd organization similar to the Masons but with fewer rules

and regulations. The group began in California in 1851. The members, known as

“Clampers”, tended to be the crowd that favored drinking, carousing and high living in

general. It suited the newly developed west. Twain and Stewart joined the group. In fact,

Stewart started the branch in Virginia City. The group had power in numbers. Some say E

Clampus Vitus helped Stewart get elected as the first Senator from Nevada.

The biggest difference between the two giants came toward the end of their

lives. Twain turned bitter and his writings reflected this. Stewart never gave up on the

dream of finding just one more big silver mine. He traipsed around Nevada on a mule

looking for silver his eighties. Stewart remained the eternal optimist.

A Formidable Political Career

Although generally regarded as a staunch Republican other than the six years he

became a member of the Silver Party, Stewart changed political parties several times

during his career. The list included Whigs, Know-Nothings, Democrats, Republicans,

Silver Party/Populists and a return to the Republicans. His beliefs changed from time to

time, but Stewart tended to be pragmatic. Even as a child Stewart loved political

excitement. In New York and Ohio the Stewart family appreciated Andrew Jackson and

Federalism. They attended July 4th events in downtown Lyons, New York cheering for

Jackson. At the age of nine, Stewart heard a speech by Joshua Giddings that proved to be

a lifelong inspiration. Giddings, a teacher turned lawyer in Ashtabula County, Ohio

championed abolitionist causes with his speeches. Joshua Giddings helped found the

Republican Party in Ohio. This was the type of personality that fired up the political

ambitions of young Stewart. Some historians call Stewart a party hopper because of his

multiple affiliations. In 1850 when he studied law with John McConnell in California, he

associated with Southern Democrats. McConnell’s office had become their local

gathering place.

Stewart refused to participate in duels, a popular activity for the Southern

Democrats. Stewart disagreed with future father-in law Henry Foote on this point. He did

not refrain from dueling out of fear, but he thought the practice to be a foolish waste of

time. Stewart embraced the Know-Nothing party briefly, a group known for being against

aliens. Stewart’s father-in-law joined the Know-Nothings. Foote influenced Stewart with

a dynamic speech he gave in Nevada City shortly after Annie and Bill married. After

Stewart joined the Republican Party in 1856, some accused him of siding with southern

sympathizers.

With the exception of the years from 1892-1898 when Stewart affiliated

himself with the Silver Party, he was a Republican during his senatorial career.

Stewart rejoined the Republicans when he finally realized the silver issue was over.

During his last bid for a Senate seat he ran as a Silver Party candidate, but shortly after

the election he was back in the Republican camp. A newspaper article in 1897 hinted that

was what he planned to do all along. He won the election despite bad press, old age and

some skullduggery. This final election was the most contentious.

At this time the State Legislatures elected the senators. Stewart became friends

with Francis Newlands when they both joined the Silver party. Stewart, twenty-one

years older than Newlands, acted as a mentor for Newlands and his political aspirations.

His first wife Clara was the daughter of Senator William Sharon. He took Stewart’s

Senate position in 1878. This friendship came to an end during the nasty Senate campaign

of 1898. Stewart astutely realized Francis Newlands wanted a Nevada Senate job –

possibly his. There were not big issues during the 1898 campaign other than silver.

Stewart managed to get Newlands kicked out of the Silver Party shortly before the

election. That did not solve all his problems. Stewart kept making speeches over and over

denying charges that he was responsible for the “Crime of “73”.

Stewart had two bodyguards during the 1898 campaign. Jack Chinn, known as a

tough guy, who always had a Bowie knife handy and David Neagle, a U.S. Marshall who

killed Judge Terry in California ten years earlier were the men who influenced the

election by either kidnapping or bribing Assemblyman William Gillespie so as not to be

present for the crucial vote for senator. That vote was fifteen to fourteen in Stewart’s

favor – thus avoiding a runoff election that Stewart might have lost. A couple months

later the absent Gillespie had a new job working for the Southern Pacific. This railroad

had great interest in Stewart’s election to keep legislation going to their benefit.

The United States was on the gold standard in 1900. The forgone conclusion became

law despite the countless speeches and tremendous effort Stewart made to avoid this.

Stewart rejoined the Republicans and turned his focus to expansionism. He considered

development of the Philippines not imperialism, but rather a way to help the people to get

established. Stewart even pushed for railroads in the Philippines. Stewart received bad

press for being a tool of the Southern Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads and

railroads in general. Stewart was not up for reelection in 1902, but he had a special

interest in the senatorial campaign. Unfortunately for him, Senator John Jones retired.

Francis Newlands wanted the job. Stewart no longer liked Newlands and hoped to force

him out of politics for good. The Southern Pacific Railroad withdrew support for Stewart

and backed Newlands. He became a senator and remained in the office until his death

in 1917. With Newlands as the junior senator, Stewart had to work with him.

Stewart did legal work on the Pious Fund Case at The Hague. California and

Mexico had been fighting over money left from the missions. Unfortunately, when he was

at The Hague his wife Annie had a fatal automobile accident in California. Although

Stewart remarried, losing Annie hit him hard. Popularity ebbed in his home state. Even

influential Republicans started to turn against him. George Nixon left the Silver Party and

rejoined the Republicans and became Stewart’s competition for the 1905 election. After

controlling Nevada politics for decades Stewart was out. He did not even participate in

the convention that could have at least paid tribute to him for his lengthy political career.

The Crime of 1873: Did He or Didn't He?

SEC.15. That the silver coins of the United States shall be a trade-dollar, a half-dollar, or fifty-cent piece, a quarter-dollar, or twenty-five cent piece, a dime, or ten-cent piece; and the weight of the trade-dollar shall be four hundred and twenty grains troy; the weight of the half-dollar shall be twelve grams (grammes) and one-half of a gram. (gramme;) the quarter-dollar and the dime shall be respectively, one-half and one-fifth of the weight of said half dollar; and said coins shall be a legal tender at their nominal value for any amount not exceeding five dollars in any one payment.

The Free Silver movement became popular after people realized what the Coinage Act

of 1873 had done - effectively demonetizing silver in this country. The term Free Silver

meant unlimited coinage of silver. Economic panics in 1873 and later in 1893 stirred up

the issue - especially in western states. The Bland-Allison Act and the Sherman Silver

Purchase Act enabled the government to buy some quantities of silver, but did not placate

the Silverites. Democratic President Grover Cleveland did not like the Sherman Act and

made sure Congress repealed it in 1873. The defeated Democratic Presidential candidate

William Jennings Bryan built his campaign around free silver in 1896. Bryan did receive

eighty-one percent of the vote in Nevada. The United States went on the gold standard in

1900. This ended the Free Silver movement.

Three years after the Coinage Act passed, Senator Stewart began to complain that

a massive crime had been committed, perpetrated by easterners and European financiers.

Stewart spoke about the silver question often, appearing as a buffoon in political cartoons.

Stewart continued his finger pointing for years, possibly for the reason of covering up

or making up for his part in demonetization. Henry Linderman, the Mint Director in

Philadelphia, created most of the wording of the act. Sherman introduced the bill in

Congress. A copy of a check indicated western banker William Ralston bribed Linderman.

Ralston papers note he paid large sums of money to Linderman. Ralston’s

Bank of California intertwined very deeply with the Comstock fortunes. When Europe

went on the gold standard, Ralston feared too much silver would be dumped in America.

Comstock silver might lose value. Ralston exerted influence on western politics. It was

well known that Stewart helped things go well for the "Bank Gang" who ran it.

Ralston liked to stay in the background, but he was the brains behind this financial

organization. According to a paper by Yale Professor Daniel Decanio, Ralston’s plan

was to have a silver trade dollar to be used in the world market, but not the United States.

He thought California’s proximity to the Asian markets would result in more money for

the Bank of California and more wealth piling up at the Comstock. By 1875 Ralston and

Linderman were dead. The Bank of California collapsed the same week as Ralston’s

death. The day he lost the title of bank president, he drowned in the Pacific Ocean – quite

possibly a suicide, but another point never proven.

With Linderman and Ralston both dead, Stewart ramped up his accusations and finger

pointing. Stewart denied knowledge of the so-called crime. It is hard to believe Stewart

did not know what was going on as the bill took three years to get through Congress.

He was exceedingly bright; few details ever escaped his eagle like mind. Stewart spent a

great deal of time blaming William Sherman, the congressman who introduced the bill.

Sherman would not go along with abolishing the coinage rate, another possible outcome

desired by Ralston. The truth of Stewart’s involvement will never be known. Senator

Stewart even rejoined the Republican party after his stint with the Silver Party.

William Morris Stewart and William Chapman knew each other quite well. Stewart

Ralston came from similar backgrounds. Both had several siblings, traveled to the

West during the gold rush and possessed insatiable desire for wealth and power.

They achieved these goals, but both had serious money problems by the end of their lives.

Ralston went west via the southern route. He stayed in Panama for five years working for

a steamship company. Stewart and Ralston could have met as Stewart journeyed through

Panama, also on the way to California. One of Ralston’s brothers purchased a Stewart

home in Carson City when the family was off to Washington D.C. Ralston parlayed his

money and by 1864 opened the Bank of California. He was always the brains behind the

operation, but chose the title of head cashier. He fell in love with San Francisco with

hopes of making it a cultural mecca of the world. This took money - and lots of it. With

William Sharon as his right hand man in Virginia City, the Bank of California invested in

the highly prized Comstock Lode. Through Sharon’s astuteness the Bank Gang from

California controlled profits from the best mines and mills. Stewart spent time in San

Francisco, learned the law profession and dabbled in mines – another opportunity for

Ralston and Stewart to know each other. Stewart relocated to Virginia City and made a

fortune settling mining disputes. Stewart represented big mining companies. Ralston and

the Bank of California owned the mines. When Nevada became a state Stewart turned to

politics. It took financial backing to win elections, and the Bank of California supported

Stewart with generous contributions. That included the payback of Stewart supporting the

bank interests. One example of Ralston influence over Stewart came when the quirky

Adolph Sutro desired to build a tunnel through Mt. Davidson for mining safety and

financial reasons. Stewart became the first president of the Sutro Tunnel Company. When

Ralston realized that the Bank would lose money if the tunnel became a reality, he turned

against it. In a short time Stewart resigned as the president and belittled the project.

Ralston liked to control political activities in Washington D.C. He often influenced

Senator Stewart to help achieve his goals. When Stewart did not prove powerful

enough to get things done Ralston’s way, his crony William Sharon received the

call to become a U.S. Senator. As it turned out, both Senator Sharon and then Senator

James Fair contributed little during Stewart’s twelve-year hiatus. When Stewart ran again,

Nevada citizens believed him to be a firm proponent of the free silver movement. Stewart

talked about the Crime of 1873 from 1876 until he became a Republican again after

William McKinley won the election in 1898. Stewart himself mentioned in a speech that

perhaps it was best not to know what had actually happened in regard to the Crime of ’73.

He could have been talking about himself.

The Free Silver movement became popular after people realized what the Coinage Act

of 1873 had done - effectively demonetizing silver in this country. The term Free Silver

meant unlimited coinage of silver. Economic panics in 1873 and later in 1893 stirred up

the issue - especially in western states. The Bland-Allison Act and the Sherman Silver

Purchase Act enabled the government to buy some quantities of silver, but did not placate

the Silverites. Democratic President Grover Cleveland did not like the Sherman Act and

made sure Congress repealed it in 1873. The defeated Democratic Presidential candidate

William Jennings Bryan built his campaign around free silver in 1896. Bryan did receive

eighty-one percent of the vote in Nevada. The United States went on the gold standard in

1900. This ended the Free Silver movement.

Three years after the Coinage Act passed, Senator Stewart began to complain that

a massive crime had been committed, perpetrated by easterners and European financiers.

Stewart spoke about the silver question often, appearing as a buffoon in political cartoons.

Stewart continued his finger pointing for years, possibly for the reason of covering up

or making up for his part in demonetization. Henry Linderman, the Mint Director in

Philadelphia, created most of the wording of the act. Sherman introduced the bill in

Congress. A copy of a check indicated western banker William Ralston bribed Linderman.

Ralston papers note he paid large sums of money to Linderman. Ralston’s

Bank of California intertwined very deeply with the Comstock fortunes. When Europe

went on the gold standard, Ralston feared too much silver would be dumped in America.

Comstock silver might lose value. Ralston exerted influence on western politics. It was

well known that Stewart helped things go well for the "Bank Gang" who ran it.

Ralston liked to stay in the background, but he was the brains behind this financial

organization. According to a paper by Yale Professor Daniel Decanio, Ralston’s plan

was to have a silver trade dollar to be used in the world market, but not the United States.

He thought California’s proximity to the Asian markets would result in more money for

the Bank of California and more wealth piling up at the Comstock. By 1875 Ralston and

Linderman were dead. The Bank of California collapsed the same week as Ralston’s

death. The day he lost the title of bank president, he drowned in the Pacific Ocean – quite

possibly a suicide, but another point never proven.

With Linderman and Ralston both dead, Stewart ramped up his accusations and finger

pointing. Stewart denied knowledge of the so-called crime. It is hard to believe Stewart

did not know what was going on as the bill took three years to get through Congress.

He was exceedingly bright; few details ever escaped his eagle like mind. Stewart spent a

great deal of time blaming William Sherman, the congressman who introduced the bill.

Sherman would not go along with abolishing the coinage rate, another possible outcome

desired by Ralston. The truth of Stewart’s involvement will never be known. Senator

Stewart even rejoined the Republican party after his stint with the Silver Party.

William Morris Stewart and William Chapman knew each other quite well. Stewart

Ralston came from similar backgrounds. Both had several siblings, traveled to the

West during the gold rush and possessed insatiable desire for wealth and power.

They achieved these goals, but both had serious money problems by the end of their lives.

Ralston went west via the southern route. He stayed in Panama for five years working for

a steamship company. Stewart and Ralston could have met as Stewart journeyed through

Panama, also on the way to California. One of Ralston’s brothers purchased a Stewart

home in Carson City when the family was off to Washington D.C. Ralston parlayed his

money and by 1864 opened the Bank of California. He was always the brains behind the

operation, but chose the title of head cashier. He fell in love with San Francisco with

hopes of making it a cultural mecca of the world. This took money - and lots of it. With

William Sharon as his right hand man in Virginia City, the Bank of California invested in

the highly prized Comstock Lode. Through Sharon’s astuteness the Bank Gang from

California controlled profits from the best mines and mills. Stewart spent time in San

Francisco, learned the law profession and dabbled in mines – another opportunity for

Ralston and Stewart to know each other. Stewart relocated to Virginia City and made a

fortune settling mining disputes. Stewart represented big mining companies. Ralston and

the Bank of California owned the mines. When Nevada became a state Stewart turned to

politics. It took financial backing to win elections, and the Bank of California supported

Stewart with generous contributions. That included the payback of Stewart supporting the

bank interests. One example of Ralston influence over Stewart came when the quirky

Adolph Sutro desired to build a tunnel through Mt. Davidson for mining safety and

financial reasons. Stewart became the first president of the Sutro Tunnel Company. When

Ralston realized that the Bank would lose money if the tunnel became a reality, he turned

against it. In a short time Stewart resigned as the president and belittled the project.

Ralston liked to control political activities in Washington D.C. He often influenced

Senator Stewart to help achieve his goals. When Stewart did not prove powerful

enough to get things done Ralston’s way, his crony William Sharon received the

call to become a U.S. Senator. As it turned out, both Senator Sharon and then Senator

James Fair contributed little during Stewart’s twelve-year hiatus. When Stewart ran again,

Nevada citizens believed him to be a firm proponent of the free silver movement. Stewart

talked about the Crime of 1873 from 1876 until he became a Republican again after

William McKinley won the election in 1898. Stewart himself mentioned in a speech that

perhaps it was best not to know what had actually happened in regard to the Crime of ’73.

He could have been talking about himself.

Scandals: The Emma , the Panamint and More

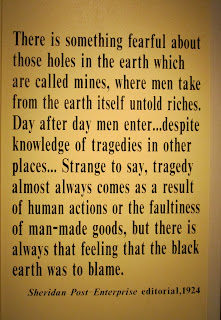

Plaque on display at the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne, Wyoming

Scandals threatened Stewart’s career in both his legal and political lives. He

made and lost fortunes along the way. Stewart had little to his name when he died. The

money came and the money went. He never had enough to keep up with his millionaire

cronies like Leland Stanford and William Ralston. Stewart invested often in mines, but it

was a risky business. The first mining disaster came in December 1861 when his

Virginia City mine flooded. Stewart took a secretive trip to San Francisco in terrible

weather to secure a loan from an old friend named Chris Reis. Census figures show

Reis in San Francisco, but not with an extensive fortune. It is conjecture, but perhaps

William Ralston might have been involved with the loan. The two could have met when

Stewart passed through Panama since Ralston worked there five years. At any rate,

Stewart headed back to Virginia City with borrowed money to settle his debts. He

eventually sold the mine and recouped most of his original investment.

The Emma Mine, located in Utah, sullied Stewart’s reputation although he avoided

legal penalties. The damage to his reputation outweighed the money he made. Ralston

had an early interest in the Emma. Neither Stewart nor Ralston could stay away from

mining ventures. Ralston could have bought the mine with his friend Asbury Harpending

for a mere three hundred and fifty thousand dollars. They decided the mine was “nothing

more than a large kidney and of little value.” Unfortunately, Stewart did not come to this

conclusion. James Lyon, two other prospectors, and Stewart worked to develop the Emma.

The others soon forgot Lyon and sought wealthy foreign investors in England. Since the

speculators spread rumors of the mine's value, many clamored to buy the stock. Lyon

hired Stewart to represent his interest in the mine. Stewart told Lyon he would get him

five hundred thousand dollars as his share. Stewart traveled to England with a speculator,

Trenor Park. In a few months Stewart appeared to be on the other side ending up as a

board member of the Emma with Park and several other well-known British

politicians. Stewart made a fortune on the deal with Lyon coming out as the big loser with

but two hundred thousand dollars as his share. Eventually news came out that the Emma

was a sham with hardly any silver. The experience spoiled English investments in North

American mines for years to come. Lyon never forgave Stewart; for years he wrote nasty

letters and filed lawsuits that never came to fruition. He claimed Stewart built the Dupont

Circle mansion with money that should have been his.

Stewart and his partner Senator John P. Jones believed the Panamint Lode located in Death

would be the new Comstock Lode. Investors from Los Angeles rather than San Francisco

financed these mines. Stewart and Jones let Trenor Park join them, despite his reputation

from the Emma Scandal.

A big problem was transportation to and from the Panamint area. Stewart and Jones

made an agreement with bank robbers. Desperadoes who discovered the silver in the first

place agreed to pay back twelve thousand dollars taken from the Wells Fargo Company.

However, the Wells Fargo Company refused to transport bullion from the two

Panamint Mines – the Wyoming and the Hemlock. Always one to think outside of the

box, Stewart had the silver bullion formed into seven hundred and fifty pound balls. The

thieves could not steal them when Stewart had large wagons move the treasure. The

rutted roads through the Sunrise Canyon out of the Panamint area caused travel to be a

challenge. Panamint investors made some money, but not enough. Production began

during August 1875. The Panamint boom lasted a mere three years and did not live up to

the lofty expectations of Stewart and Jones.

The Women in His Life

Miranda Morris Stewart influenced her son in positive ways. She valued education, a

trait her husband did not share. In dedication of his autobiography Stewart wrote, “If I had

always kept in view the rules of conduct which she prescribed I would have made few

mistakes.” Stewart went on to say “Whatever of good I may have accomplished was

inspired by my dear mother at an early period of my existence.” Three daughters and an

outspoken, well-educated wife influenced him to believe in women’s rights before it

became popular. Love and loyalty to family members were high priorities throughout his

entire life.

To understand Annie Stewart's complex personality, one needs to examine her genteel

Mississippi upbringing. The new baby Foote was born on June 8, 1826. Her father, Henry

S. Foote, farmed cotton on the plantation, practiced law and owned a local newspaper.

The entire population, including the slaves, celebrated as Annie Foote joined her two

Virginia and Arabella Foote. The girls grew up wanting for nothing. Annie showed

spunk and independence, qualities admired by her father, Henry Stuart Foote. Henry

made sure his daughters received first-rate educations. The children studied classical

languages, dancing, etiquette, and learned to sew and produce fine handwork. Foote

supervised the education, frequently testing them. Annie Foote rebelled when it came to

the sewing projects, but tackled the academics with gusto. Annie’s spirit endeared her to

her father. Foote's clear favorite, Annie Foote spent more time with her father than she

did with her sisters. When Foote became a United States Senator and the family moved to

Washington D. C., Annie Foote adapted well. She attended the Visitation Convent

and spent most of her teenage years in Washington D.C.

When Foote’s term as Senator ended he and the family returned to Mississippi.

Foote continued his political career by running for the governorship. He beat out

Jefferson Davis. Davis pulled political maneuvers tha eliminated Foote's chances for

re-election to the Senate. Foote moved his family to Raymond, Mississippi, leaving them

there while he made a trip to California to seek his next fortune.

Men often traveled west first to prepare the way for spouses and children. Foote built a

home on five acres near Oakland, California. He constructed a house exactly the

same as the one in Clinton, Mississippi. When he finished, he sent for his family to join

him. The Foote entourage took the southern route across Panama to California. The group

included mother Elizabeth, her children Virginia, Arabella, Annie, Jane, Henry, Romily

and William as well as the family servants. With natives paddling, they crossed the

Isthmus of Panama in small boats. The Foote family braved the jungle elements, and

arrived in California in November of 1854. Foote and young William Morris Stewart

became law partners; consequently, he received invitations to Foote social events.

Annie Foote and William Stewart became a couple in no time. Foote approved of his

daughter's match with his young law partner. Less than a year later on May 31, 1855 the

young couple married.

Always in search of a fortune, Stewart could not resist the call of mining and a town

needing lawyers. He gave up his practice in San Francisco, and the newlyweds moved to

Nevada City, California. Stewart knew it would be a hardship on his wife to leave her

life for a mining camp lacking comforts and high society. As his father-in-law

mentor father-in-law had done, he replicated her Mississippi home in Nevada City as a

wedding gift. He imported the materials from the South to make it more authentic. The

clever Stewart built the house on Piety Hill, because he knew of the fire dangers of

downtown locations. The Piety Hill home became the new place to be seen with Annie

Stewart at the center of local society. Records are sketchy because of a fire in Nevada

City, but the Stewarts had a baby girl named Elizabeth (Bessie) on or about August

18,1856.

No sooner did Annie get used to her new home than Bill Stewart yearned to move.

Downieville peaked his interest after a year and a half. Like his father-in-law he went first,

established his law office and home before moving Annie and little Bessie. During this

time he made frequent trips to Downieville, Nevada City and San Francisco. He often

brought books to Annie. Bessie and Annie finally moved to Downieville in the spring of

1858. Similar to the trip over the Isthmus of Panama, moving proved to be a hardship.

Transporting Annie's possessions and furniture was not easy. During the time in

Downieville Annie had parties, entertained, established a school and became a teacher.

The eight hundred dollars she made teaching was the only paid job she ever held.

Another child, Anna, was born in 1859. By 1860 the Stewarts moved again – this

time to Virginia City, Nevada. The Comstock era of silver mining began with a rough

camp with few luxuries. Annie Stewart accepted the challenges. When Stewart's wife

talked, people noticed. Her outspoken words favoring the South caused problems.

When Stewart campaigned for statehood, he wanted his wife out of the way for a while.

He gave her forty thousand dollars and told her to go shopping in San Francisco. With her

pockets laden with cash, Annie Stewart left on the earliest stage she could. The only thing

she liked more than talking and entertaining was shopping. This penchant for shopping

was was a big reason William Stewart found himself in financial difficulty over the years.

Despite the many fortunes he accrued, Annie Stewart shopped faster than her husband

could make money.

Annie Stewart enrolled the girls in expensive private schools in Europe. Bessie and

Anna spent two years each in France, Germany and Italy getting a proper, classical

education. Annie had another reason for traveling to Europe. Her father, a southern

sympathizer, had been exiled to Europe from the United States after the Civil War

because of war crimes. Throughout their long years together, Stewart tried to please his

wife at any cost.

When Annie Stewart returned to the states she busied herself decorating, socializing at

the Dupont Circle home in Washington D. C. She also traveled; Mary Isabelle, known as

Maybelle, was born September 30, 1872 in Alameda, California during an extended visit

to California. Stewart opted not to run for the Senate in 1875, and the family returned to

the West so he could regenerate his fortunes through law and mining. The Stewarts

divided their time between the eastern and western regions of the country. On December

30, 1879 a fire caused major damage at the Dupont Circle home. Servants saved

six-year-old Maybelle as both her parents were not home the night of the fire. After the

fire Anne took more trips abroad to replaced damaged items.

Bessie, Annie and Maybelle Stewart had the same impulsive tendencies as their

father. When unfortunate things happened, Stewart was there to fix the problems. Anna

had a messy divorce with Andrew Fox. Stewart did not like how Anna and Andrew Fox

took care of their four children after the divorce. Stewart kidnapped the children and kept

them at an undisclosed location in the East for several months. One of the children died

during this period. Fox had custody of the children and cited Stewart for contempt.

Nothing became of this other than Stewart received temporary custody of the children.

In 1902 William Morris Stewart was in his last term as a U.S. Senator. He left

for Europe in September to work on the Pious Fund Case at The Hague. Originally, Annie

planned to accompany her husband on the trip. She thought she would be helpful with her

knowledge of foreign languages. She did not feel well and decided to visit friends and

relatives in California while Stewart worked in Europe. This proved to be a bad choice.

On September 12th Annie took an automobile ride with her nephew Charles Foote and

his brother-in-law H. Benedict Taylor. Taylor owned the Winton auto involved in a

deadly crash. Taylor drove the automobile into a telegraph pole while trying to avoid a

grocery wagon. The accident happened at Bay Street and Santa Clara in Alameda,

California at 4:30PM. Witnesses had different takes on what happened. Speeding,

carelessness and perhaps alcohol might have been to blame. Neither young man suffered

debilitating injuries even though they all flew out of the automobile upon the impact of

hitting the pole. Passersby took Annie to a house until the ambulance came to take her to

the Alameda Sanatorium. She died at 6:00 of massive internal injuries. Annie was 64

years old. Taylor only had the automobile for a couple weeks. It had been manufactured

in Cleveland, Ohio. A jury cleared Taylor of blame in the accident. Taylor stated he only

had a speed of fifteen miles per hour. Stewart declared this was the greatest tragedy of his

life when he received the news. Stewart cabled to have a service, but hold the body until

his arrival home. The family held a service at the Foote home with Rev. Robert Ritchie, an

Episcopal priest presiding. A few close friends and family members attended the service.

The casket stayed at the Mountain View Cemetery until Stewart arrived a couple weeks

later.

Losing the love of his life devastated Stewart. However, he did marry again on

October 26, 1903 to a widow named May Agnes Cone. Despite the age difference of over

thirty years, the couple lived a happy life until Stewart’s death in 1909. May Agnes and

her nine year old daughter Vera followed Stewart to a remote town in Nevada where

Stewart attempted to find just one more silver mine.

trait her husband did not share. In dedication of his autobiography Stewart wrote, “If I had

always kept in view the rules of conduct which she prescribed I would have made few

mistakes.” Stewart went on to say “Whatever of good I may have accomplished was

inspired by my dear mother at an early period of my existence.” Three daughters and an

outspoken, well-educated wife influenced him to believe in women’s rights before it

became popular. Love and loyalty to family members were high priorities throughout his

entire life.

To understand Annie Stewart's complex personality, one needs to examine her genteel

Mississippi upbringing. The new baby Foote was born on June 8, 1826. Her father, Henry

S. Foote, farmed cotton on the plantation, practiced law and owned a local newspaper.

The entire population, including the slaves, celebrated as Annie Foote joined her two

Virginia and Arabella Foote. The girls grew up wanting for nothing. Annie showed

spunk and independence, qualities admired by her father, Henry Stuart Foote. Henry

made sure his daughters received first-rate educations. The children studied classical

languages, dancing, etiquette, and learned to sew and produce fine handwork. Foote

supervised the education, frequently testing them. Annie Foote rebelled when it came to

the sewing projects, but tackled the academics with gusto. Annie’s spirit endeared her to

her father. Foote's clear favorite, Annie Foote spent more time with her father than she

did with her sisters. When Foote became a United States Senator and the family moved to

Washington D. C., Annie Foote adapted well. She attended the Visitation Convent

and spent most of her teenage years in Washington D.C.

When Foote’s term as Senator ended he and the family returned to Mississippi.

Foote continued his political career by running for the governorship. He beat out

Jefferson Davis. Davis pulled political maneuvers tha eliminated Foote's chances for

re-election to the Senate. Foote moved his family to Raymond, Mississippi, leaving them

there while he made a trip to California to seek his next fortune.

Men often traveled west first to prepare the way for spouses and children. Foote built a

home on five acres near Oakland, California. He constructed a house exactly the

same as the one in Clinton, Mississippi. When he finished, he sent for his family to join

him. The Foote entourage took the southern route across Panama to California. The group

included mother Elizabeth, her children Virginia, Arabella, Annie, Jane, Henry, Romily

and William as well as the family servants. With natives paddling, they crossed the

Isthmus of Panama in small boats. The Foote family braved the jungle elements, and

arrived in California in November of 1854. Foote and young William Morris Stewart

became law partners; consequently, he received invitations to Foote social events.

Annie Foote and William Stewart became a couple in no time. Foote approved of his

daughter's match with his young law partner. Less than a year later on May 31, 1855 the

young couple married.

Always in search of a fortune, Stewart could not resist the call of mining and a town

needing lawyers. He gave up his practice in San Francisco, and the newlyweds moved to

Nevada City, California. Stewart knew it would be a hardship on his wife to leave her

life for a mining camp lacking comforts and high society. As his father-in-law

mentor father-in-law had done, he replicated her Mississippi home in Nevada City as a

wedding gift. He imported the materials from the South to make it more authentic. The

clever Stewart built the house on Piety Hill, because he knew of the fire dangers of

downtown locations. The Piety Hill home became the new place to be seen with Annie

Stewart at the center of local society. Records are sketchy because of a fire in Nevada

City, but the Stewarts had a baby girl named Elizabeth (Bessie) on or about August

18,1856.

No sooner did Annie get used to her new home than Bill Stewart yearned to move.

Downieville peaked his interest after a year and a half. Like his father-in-law he went first,

established his law office and home before moving Annie and little Bessie. During this

time he made frequent trips to Downieville, Nevada City and San Francisco. He often

brought books to Annie. Bessie and Annie finally moved to Downieville in the spring of

1858. Similar to the trip over the Isthmus of Panama, moving proved to be a hardship.

Transporting Annie's possessions and furniture was not easy. During the time in

Downieville Annie had parties, entertained, established a school and became a teacher.

The eight hundred dollars she made teaching was the only paid job she ever held.

Another child, Anna, was born in 1859. By 1860 the Stewarts moved again – this

time to Virginia City, Nevada. The Comstock era of silver mining began with a rough

camp with few luxuries. Annie Stewart accepted the challenges. When Stewart's wife

talked, people noticed. Her outspoken words favoring the South caused problems.

When Stewart campaigned for statehood, he wanted his wife out of the way for a while.

He gave her forty thousand dollars and told her to go shopping in San Francisco. With her

pockets laden with cash, Annie Stewart left on the earliest stage she could. The only thing

she liked more than talking and entertaining was shopping. This penchant for shopping

was was a big reason William Stewart found himself in financial difficulty over the years.

Despite the many fortunes he accrued, Annie Stewart shopped faster than her husband

could make money.

Annie Stewart enrolled the girls in expensive private schools in Europe. Bessie and

Anna spent two years each in France, Germany and Italy getting a proper, classical

education. Annie had another reason for traveling to Europe. Her father, a southern

sympathizer, had been exiled to Europe from the United States after the Civil War

because of war crimes. Throughout their long years together, Stewart tried to please his

wife at any cost.

When Annie Stewart returned to the states she busied herself decorating, socializing at

the Dupont Circle home in Washington D. C. She also traveled; Mary Isabelle, known as

Maybelle, was born September 30, 1872 in Alameda, California during an extended visit

to California. Stewart opted not to run for the Senate in 1875, and the family returned to

the West so he could regenerate his fortunes through law and mining. The Stewarts

divided their time between the eastern and western regions of the country. On December

30, 1879 a fire caused major damage at the Dupont Circle home. Servants saved

six-year-old Maybelle as both her parents were not home the night of the fire. After the

fire Anne took more trips abroad to replaced damaged items.

Bessie, Annie and Maybelle Stewart had the same impulsive tendencies as their

father. When unfortunate things happened, Stewart was there to fix the problems. Anna

had a messy divorce with Andrew Fox. Stewart did not like how Anna and Andrew Fox

took care of their four children after the divorce. Stewart kidnapped the children and kept

them at an undisclosed location in the East for several months. One of the children died

during this period. Fox had custody of the children and cited Stewart for contempt.

Nothing became of this other than Stewart received temporary custody of the children.

In 1902 William Morris Stewart was in his last term as a U.S. Senator. He left

for Europe in September to work on the Pious Fund Case at The Hague. Originally, Annie

planned to accompany her husband on the trip. She thought she would be helpful with her

knowledge of foreign languages. She did not feel well and decided to visit friends and

relatives in California while Stewart worked in Europe. This proved to be a bad choice.

On September 12th Annie took an automobile ride with her nephew Charles Foote and

his brother-in-law H. Benedict Taylor. Taylor owned the Winton auto involved in a

deadly crash. Taylor drove the automobile into a telegraph pole while trying to avoid a

grocery wagon. The accident happened at Bay Street and Santa Clara in Alameda,

California at 4:30PM. Witnesses had different takes on what happened. Speeding,

carelessness and perhaps alcohol might have been to blame. Neither young man suffered

debilitating injuries even though they all flew out of the automobile upon the impact of

hitting the pole. Passersby took Annie to a house until the ambulance came to take her to

the Alameda Sanatorium. She died at 6:00 of massive internal injuries. Annie was 64

years old. Taylor only had the automobile for a couple weeks. It had been manufactured

in Cleveland, Ohio. A jury cleared Taylor of blame in the accident. Taylor stated he only

had a speed of fifteen miles per hour. Stewart declared this was the greatest tragedy of his

life when he received the news. Stewart cabled to have a service, but hold the body until

his arrival home. The family held a service at the Foote home with Rev. Robert Ritchie, an

Episcopal priest presiding. A few close friends and family members attended the service.

The casket stayed at the Mountain View Cemetery until Stewart arrived a couple weeks

later.

Losing the love of his life devastated Stewart. However, he did marry again on

October 26, 1903 to a widow named May Agnes Cone. Despite the age difference of over

thirty years, the couple lived a happy life until Stewart’s death in 1909. May Agnes and

her nine year old daughter Vera followed Stewart to a remote town in Nevada where

Stewart attempted to find just one more silver mine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)